Three Lessons from Pay for Success Investing

This blog originally appeared in Opportunity Finance Network’s January 24, 2017 digest.

Pay for Success projects are underway in communities across the country -- providing homes for struggling families, job training to people with steep barriers to employment, and high-quality education to children in low-income neighborhoods. CDFIs have played a critical role in developing the U.S. Pay for Success market. Beyond the benefits that the limited number of active projects are delivering to people in need, Pay for Success (PFS) is important as a model for approaches to funding social change based on measurable results. In 2013, Nonprofit Finance Fund committed to investing over $1 million in PFS projects across a range of issue areas and geographies. These investments have informed our advisory work, influenced the development of the recently revamped Pay for Success Learning Hub as a field resource, and deepened our understanding of a tool that has drawn much attention in the world of social-sector financing.

A few years and several investments later, here are three observations for CDFIs considering involvement in Pay for Success.

PFS Investing Requires New Skills and Flexibility

As I wrote earlier this year, investors have to reconfigure their tools when evaluating PFS projects. Underwriting an organization’s management, operating environment, and project plans may be familiar territory, but assessing scientific evidence, evaluation designs, and financial models built around social outcomes is another story. Not all CDFIs will have the in-house capacity to underwrite each of these elements and may rely on outside consultants or even other investors with complementary subject-matter expertise and experience with PFS. With that in mind, NFF and other investors are using their experience to develop frameworks for underwriting, structuring, and documentation that may help establish more efficiency and reduce barriers for new entrants to the PFS field.

Projects are Time-Intensive, and the Closing is Just the Beginning

While some consistency has emerged around things like financial returns, termination events, and lenders’ rights and remedies, PFS investments are still far more customized than standardized, and are often time-intensive to close as a result. Even after a project launches, issues are likely to arise that require additional attention. For example, if enrollment fails to meet benchmarks or early indicators of outcomes are below expectations, the PFS contract may require lender consent to make adjustments to the program and contract. While asset management of these investments can be time consuming, most CDFIs already have experience managing complicated, multi-stakeholder transactions. Think New Markets Tax Credits, public-private partnerships, and place-based financing strategies.

Thus far, capital availability has been somewhat constrained because of the significant time and capacity required, but as PFS contracts and processes move toward standardization, CDFIs may be well positioned to leverage their experience managing complex investments to play a bigger role in this market.

Outcomes Pricing Isn’t Standard

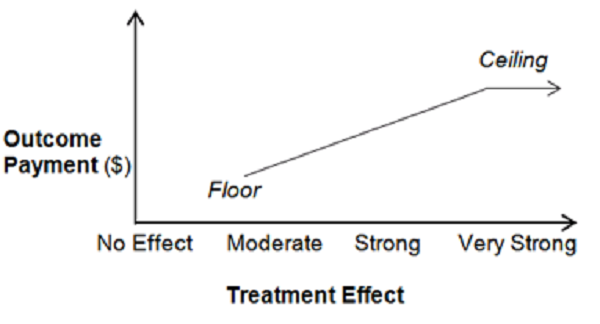

Outcomes pricing refers to the payment schedule that determines when and how investors get repaid by the end payor -- most often government. There are several elements to outcomes pricing beyond simply the amount paid per outcome, including but not limited to: 1) the floor and ceiling of the payment curve, 2) the shape of the payment curve, and 3) the timing and frequency of payments.

Regarding the floor, the payor may only be willing to pay for positive outcomes in excess of a certain threshold of success. For example, a government could determine that payments may only be made if there is a 20% improvement in the desired social outcome because that is the threshold for attributing success to the intervention without the risk of paying for too much statistical noise.

On the other end, the ceiling of the payment curve is often high enough to help create a financial incentive for investors to take outcomes risk. For example, a $10 million project might have a $12 million PFS contract so that if the treatment effect is very strong, investors can get their $10 million back plus up to $2 million from the additional savings or benefit realized by the payor.

To complicate matters, that line between the payment floor and ceiling is not always straight. Payors may allow a pricing schedule where the curve has a steeper slope up to the point where investors break even, with a flatter curve applied to any additional marginal benefit or savings.

Finally, some projects have been structured around multiple outcomes that can trigger payments at different times. For example, in one of the projects NFF is supporting, some lenders invested in outcomes that will be measured periodically and therefore may generate cash flow throughout the term of the project, while others invested in outcomes being measured at the conclusion of the project, so they will only be able to receive payments upon the final evaluation.

What Now?

The promise of Pay for Success is not in the financing mechanism, per se. It’s in the power to encourage governments, funders, and service providers to pursue partnerships toward shared goals of evidence-based policy and funding what works. In today’s polarized political climate, PFS stands out as a unique approach with bipartisan support for its dual focus on improving social outcomes and efficient use of public funds.

Investing in these “first generation” PFS projects has reinforced for us the complexity involved and the resources required to lay the groundwork for this paradigm shift toward outcome-based funding. Our experience over these past couple of years has left us optimistic that next-generation models might leverage the time and creativity we’ve already invested to support positive outcomes for people who are most overlooked and underserved by the status quo.